Technical development in the major cities of the Romans

- Written by Portal Editor

The supply of the larger cities of the Roman Empire - Rome already had 800,000 inhabitants in the first century AD - could only be ensured through structural adjustment of the surrounding rural regions, in the course of which rural estates close to the city or on trade routes began to meet the growing demand through market-oriented forms of production.

Very often this was associated with a specialization in certain agricultural products such as wine or olive oil (the latter was also used for lighting purposes). There were first approaches to the division of labour here. While slaves made up the majority of agricultural workers, the peak demand for labour during harvest times was also met by free small farmers and day labourers. Additionally, extensive imports from other parts of the empire were required to meet Rome's needs for grain, oil, and wine.

Human andanimal muscle power and water power

Five different sources of energy were available in the Roman Empire: human muscle power, animal muscle power, hydropower (since the Principate of Augustus), wood and charcoal as fuels, and wind energy. The latter was only used in shipping; it played no role on land - probably because the rapidly changing wind directions were viewed as an obstacle.

Five different sources of energy were available in the Roman Empire: human muscle power, animal muscle power, hydropower (since the Principate of Augustus), wood and charcoal as fuels, and wind energy. The latter was only used in shipping; it played no role on land - probably because the rapidly changing wind directions were viewed as an obstacle.

Steam power was also not used for production processes, although it was already theoretically known in the Hellenistic world. The low level of mechanization of the Roman economy meant that replacing manual labour with the development of new energy sources and the associated use of machines did not appear to be a conceivable step towards increasing productivity.

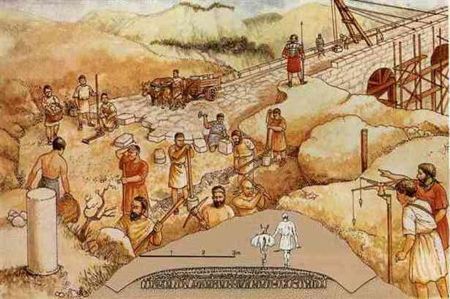

Many devices were powered by human muscle power - the potter's wheel as well as the cranes of the Roman construction industry, which often moved heavy loads with the help of pedal wheels.

Many devices were powered by human muscle power - the potter's wheel as well as the cranes of the Roman construction industry, which often moved heavy loads with the help of pedal wheels.

Although merchant ships used sails to use the wind to move, warships, which had to manoeuvre independently of the wind, were powered by rowers, as were many cargo ships and boats.

Goods were also mostly transported within Roman cities by human porters. Due to the often-narrow streets, sedan chairs were the preferred means of transport for the wealthy.

Oxen, donkeys and mules – for transport purposes

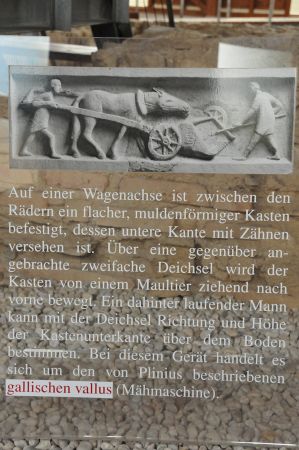

As in the entire Mediterranean region, the pulling and carrying power of animals - especially oxen, donkeys and mules - was used in the Roman Empire for agricultural and transport purposes. The use of horses was initially limited to the military and circus sectors, but they increasingly played a role in transport.

As in the entire Mediterranean region, the pulling and carrying power of animals - especially oxen, donkeys and mules - was used in the Roman Empire for agricultural and transport purposes. The use of horses was initially limited to the military and circus sectors, but they increasingly played a role in transport.

Even before the transition to a manufacturing economy (Neolithic), grinding stones were part of the Mesolithic culture. The already well-known mortar was later replaced by hand-driven rotary mills. In Roman times, large mills (Göpel) are known from Pompeii, for example, which were operated with mules.

Hydropower has been used since Roman times. The Roman engineer Vitruvius planned the mills, for example the Karlsmühle as a stone mill for cutting marble blocks on the Ruwer near Trier/Moselle.

Hydropower has been used since Roman times. The Roman engineer Vitruvius planned the mills, for example the Karlsmühle as a stone mill for cutting marble blocks on the Ruwer near Trier/Moselle.

Thanks to improved grain mills - the so-called "Pompeian mill" used the principle of rotational movement for the first time - donkeys and horses could now be used instead of human workers for the laborious and monotonous work of grinding grain. Old and weakened animals were often used to move the grain mills.

Palladius recommended that landowners build water-powered mills

Roman sources provide evidence of the use of water power for pumping water with bucket wheels and for water mills. Vitruvius describes bucket wheels driven by the current of a river. This was a simpler mechanism in which the drive wheel also served as a bucket wheel. Water mills were more complex in design - in order to be able to transfer the rotational movement to the millstone, a corresponding mechanism in the form of gears was required.

Roman sources provide evidence of the use of water power for pumping water with bucket wheels and for water mills. Vitruvius describes bucket wheels driven by the current of a river. This was a simpler mechanism in which the drive wheel also served as a bucket wheel. Water mills were more complex in design - in order to be able to transfer the rotational movement to the millstone, a corresponding mechanism in the form of gears was required.

In Rome, a large number of water mills were built on the slopes of the Ianiculum on the Tiber and fed by an aqueduct. In late Roman times, a similar complex with eight mill houses on a steep slope was built near Arles. Here too, the constant flow of water was ensured by an aqueduct. Palladius recommended that landowners build water-powered mills in order to be able to grind grain independently of human or animal labour.

Antique operation of water-powered marble saws

After the mills on the Ianiculum were destroyed during the Goth invasion in 537, water mills were installed on two permanently moored ships on the orders of the general Belisarius. The strong current of the Tiber created ideal conditions for the use of such ship mills, so their number was quickly increased to ensure the supply of the Roman population.

After the mills on the Ianiculum were destroyed during the Goth invasion in 537, water mills were installed on two permanently moored ships on the orders of the general Belisarius. The strong current of the Tiber created ideal conditions for the use of such ship mills, so their number was quickly increased to ensure the supply of the Roman population.

Apart from grinding grain, water power was also used in Roman antiquity to saw blocks of stone and marble. The mechanical sawing of marble was not possible with the usual rotational movement of water mills; What was required was a back-and-forth movement. Such a transmission mechanism was first detected in the sawmill of Hierapolis (late 3rd century AD). Similar power transmission mechanisms with a crank and connecting rod, although without a gear drive, are known from archaeological excavations of two stone sawmills from the 6th century AD in Gerasa (Jordan) and Ephesus (Turkey).

Written evidence of the ancient operation of water-powered marble saws near Trier can be found in Ausonius' poem Mosella from the late 4th century AD. A passage written around the same time in the work of Saint Gregory of St Nyssa indicates the existence of marble sawmills in the Anatolian region, so it can be assumed that such industrial mills were widespread in the late Roman Empire.

Remains of the oldest Roman stone mill north of the Alps were found near the mill. Mills were built at that time by the Roman engineer Vitruvius. In 371 AD, the Roman writer Ausonius wrote in his poem Mosella: The Ruwer turns the grain-grinding stones in dizzying whirls and pulls the screaming saws through smooth blocks of marble.

Please read as well:

Roman artifacts in the school museum at Kalishta

Roman Scupi - first settlement in the history of Skopje

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

-

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

Ölpresse Salona & Deokletianspalast Split

https://www.alaturka.info/en/history/antiquity/6419-technical-development-in-the-major-cities-of-the-romans#sigProIdef4a496136