Klis Fortress - bulwark to the Split peninsula

- Written by Portal Editor

The first point of our sightseeing program was scheduled early the next morning, which was to lead to the castle and fortress of Klis. The fortress has always played a crucial role in the eventful history of Split and the surrounding area, as it was the first place to pass if you wanted to get from the hinterland to the coast.

This was true for both the Illyrians and later the Romans, because from here the road from Salona to the interior could be easily monitored. Later, when it was of little importance during the migration period, Klis Castle was rebuilt in the 9th century by the Croatian Prince Trpimir I. In the following centuries, the place repeatedly served as a residence for the Croatian kings.

Klis owned by the Croatian noble family Šubić

After some in-depth explanations about the 2014 olive harvest, which was almost completely cancelled due to the climatic conditions, as well as the possible economic effects for the entire region, we then went steadily uphill on side roads to the parking lot below the fortress. The many phone calls that Robi made during the journey were almost Turkish. Only later would we find out against what background this happened. We set off on the short climb to the fortress, listening carefully to Robi's explanations.

After some in-depth explanations about the 2014 olive harvest, which was almost completely cancelled due to the climatic conditions, as well as the possible economic effects for the entire region, we then went steadily uphill on side roads to the parking lot below the fortress. The many phone calls that Robi made during the journey were almost Turkish. Only later would we find out against what background this happened. We set off on the short climb to the fortress, listening carefully to Robi's explanations.

In the 13th century, Klis came into the possession of the Croatian noble family Šubić. As the family with Mladen III. Šubić died out in 1354, the Bosnian Ban Tyrtko was supposed to take possession of the fortress for the Hungarian king. He was preceded by the Serbian Tsar Stephan Dušan, whose troops occupied Klis in 1355. After Dušan's death in the same year, Klis was alternately under Hungarian and Bosnian rule, but was always given as a fief to a Croatian noble.

Ottoman Empire in 1463 Bosnia

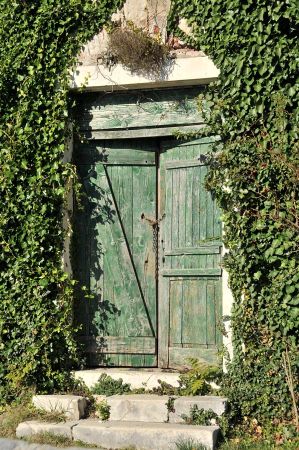

In the meantime, another person had arrived at the castle gate and so we found out the background to some of the phone calls. The castle gate was locked and the colleague brought the key. To shorten it: In the coming days we were to experience a few surprises in the organization, which were briefly clarified over the phone, so we had access to the various museums, city archives, and even the monastery.

In the meantime, another person had arrived at the castle gate and so we found out the background to some of the phone calls. The castle gate was locked and the colleague brought the key. To shorten it: In the coming days we were to experience a few surprises in the organization, which were briefly clarified over the phone, so we had access to the various museums, city archives, and even the monastery.

Once you entered the first gate of the fortress, it became clear that the location of this castle complex was considered almost impregnable. Two more gates followed, with things going steadily uphill on a narrow gradient. The floor plan is a very narrow but elongated complex, which is a maximum of 30 meters wide. Very easy to defend if there are enough provisions available. Robi also had a lot of details about the Ottomans and often jokingly talked to Seher about the "enemies", of which she was one. In short, the visit to the fortress, as well as all the other short stays later, turned out to be absolutely informative without the flow of information ever becoming too much. But more on that later.

After the Ottoman Empire conquered Bosnia in 1463 and a little later also Herzegovina (1482), attacks on Spalatines in the city's countryside increased (according to the name of the city of Split in Roman times "Spalato/um"), its residents called themselves Spalatinians). Although Venice was able to force the Ottomans to make peace in various wars (Third Ottoman-Venetian War 1499–1503), the raids on Spalato and other Venetian protectorates continued.

After the Ottoman Empire conquered Bosnia in 1463 and a little later also Herzegovina (1482), attacks on Spalatines in the city's countryside increased (according to the name of the city of Split in Roman times "Spalato/um"), its residents called themselves Spalatinians). Although Venice was able to force the Ottomans to make peace in various wars (Third Ottoman-Venetian War 1499–1503), the raids on Spalato and other Venetian protectorates continued.

In 1522 the Ottomans tried to take the fortress of Klis above Spalatos, which was repelled with the support of Archbishop Tommaso de Nigris (Toma Nigris). The Spalatin humanists Marcus Marulus Spalatensis (Marko Marulić/Marco Marulo) and Franciscus Natalis (Franjo Božičević Natalis) underpinned the anti-Ottoman sentiment in the city. Petar Kružić (Peter Krusitsch), captain of the Klis Fortress, had fended off Ottoman attacks for more than 20 years when he fell in 1537 in the course of the Fourth Ottoman-Venetian War (1537–1540) and with him the fortress, which was henceforth known as Ottoman served as an outpost for attacks on Spalato.

The most important trade route ran from Split via Klis to Sarajevo

In the course of the Fifth Ottoman-Venetian War (over Cyprus) in 1571, parts of the city's land area, including Solin and Kamen (Sasso di Spalato), fell to the Turks. An attempt to recapture it failed. At the beginning of the 1570s, a Jewish-Sephardic community was founded in the city, in the northwestern part of the palace district, whose cemetery on Marjan, which was laid out in 1573, still exists today.

In the course of the Fifth Ottoman-Venetian War (over Cyprus) in 1571, parts of the city's land area, including Solin and Kamen (Sasso di Spalato), fell to the Turks. An attempt to recapture it failed. At the beginning of the 1570s, a Jewish-Sephardic community was founded in the city, in the northwestern part of the palace district, whose cemetery on Marjan, which was laid out in 1573, still exists today.

The Ottomans built a mosque and made Klis the centre of a sanjak. From Klis, Ottoman troops threatened Venetian Dalmatia for a long time. In 1596 the Venetians succeeded in conquering Klis for the first time; However, they had to vacate the fortress again after a short time. Despite the often-hostile relationship between the Republic of St. Mark and the Ottomans, trade between the Dalmatian coast and the interior of the Balkans was never interrupted for long. The most important trade route ran from Split via Klis to Sarajevo. Both Dalmatian and Turkish merchants travelled this route with donkey caravans. In 1648, the Venetians were able to conquer Klis again during the War of Candia under the command of Leonardo Foscolo. While Crete had to be abandoned at the same time, the Republic of Klis was preserved under the peace treaty of 1669.

Fortress builder Alessandra Maglio built mighty bastions

The plague killed 7,000 of the 10,000 inhabitants at the end of the 16th century; after another epidemic in 1607, only 1,400 Spalatinians remained. Further wars (Sixth Ottoman-Venetian War (over Crete), 1645-1669, and Seventh Ottoman-Venetian War (Great Turkish War), 1684-1699) affected Spalato's development and contributed to the decline of Venice and its possessions.

The plague killed 7,000 of the 10,000 inhabitants at the end of the 16th century; after another epidemic in 1607, only 1,400 Spalatinians remained. Further wars (Sixth Ottoman-Venetian War (over Crete), 1645-1669, and Seventh Ottoman-Venetian War (Great Turkish War), 1684-1699) affected Spalato's development and contributed to the decline of Venice and its possessions.

After all, in 1645, General Leonardo Foscolo managed to wrest the Klis fortress from the Ottomans, which from then on was able to prevent Ottoman incursions into the city's countryside. But in 1657 Hersekli Ahmed Paşa once again penetrated the countryside right up to the city walls.

The fortress architect Alessandra Maglio then built mighty bastions and ramparts around the city, as mapped by Giuseppe Santini in 1666.

With the gradual pushback of the Ottomans in the early 18th century, the threat also moved far away from Spalato's land area. With the end of the Republic of Venice, which Napoleon brought about in 1797, Austria took over its Dalmatian possessions, including Spalato. But this did not last long, because in 1806 General Lauriston captured Spalato for the French Illyrian Provinces (1807–1813). In 1806 and 1807, on the orders of Auguste Viesse de Marmont, the demolition of the ramparts and bastions began, which was completed in the following Austrian period.

With the gradual pushback of the Ottomans in the early 18th century, the threat also moved far away from Spalato's land area. With the end of the Republic of Venice, which Napoleon brought about in 1797, Austria took over its Dalmatian possessions, including Spalato. But this did not last long, because in 1806 General Lauriston captured Spalato for the French Illyrian Provinces (1807–1813). In 1806 and 1807, on the orders of Auguste Viesse de Marmont, the demolition of the ramparts and bastions began, which was completed in the following Austrian period.

During the first tour we had already received a rough overview of the historical processes, for which we were very grateful. People increasingly had the feeling that they could better identify the connections between the historical buildings, the natural landscape and their inhabitants. From now on it should be about antiquity and what could still emerge in the region around Split.

Klis Fortress – The Bulwark of the Split Peninsula more details

Perched high on a rocky ridge, the imposing Klis Fortress is one of Croatia's most fascinating historical monuments. For centuries, it played a pivotal role in the region's defense and served as a protective shield for the city of Split.

Perched high on a rocky ridge, the imposing Klis Fortress is one of Croatia's most fascinating historical monuments. For centuries, it played a pivotal role in the region's defense and served as a protective shield for the city of Split.

But the fortress is more than just a military outpost – it is a symbol of resistance, a cultural heritage site, and a breathtaking vantage point with panoramic views of the Dalmatian coast. Join us on a journey through Klis's rich history and discover why a visit to this medieval fortress is worthwhile.

1. The Strategic Importance of Klis Fortress

1.1. Why Was Klis Fortress Built?

Klis Fortress was built on a natural rocky ridge and was ideally suited for defense. Its location between the Dinaric Alps and the Adriatic Sea made it an important strategic point for controlling the Dalmatian coast.

1.2. Who Built the Fortress?

The fortress's origins date back to the Illyrians, who built a fortification here in the 2nd century BC. Later, the Romans, Byzantines, Croats, and Ottomans expanded the complex, making it one of the region's most important castles for centuries.

The fortress's origins date back to the Illyrians, who built a fortification here in the 2nd century BC. Later, the Romans, Byzantines, Croats, and Ottomans expanded the complex, making it one of the region's most important castles for centuries.

2. The History of Klis Fortress – A Bulwark Against Invaders

2.1. The Romans and Byzantines – The First Great Rulers

After the Romans gained control of Dalmatia in the 1st century AD, Klis became an important defensive fortification against barbarian tribes. After the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Byzantines took over the castle in the 6th century, thus securing the region.

2.2. The Croatian Kingdom – Klis as the Seat of Rulers

In the 9th century, Klis became the residence of Croatian princes. The castle gained particular importance under Prince Trpimir I (reigned from 845–864). This is where one of the first mentions of the name "Croatia" in historical documents originated.

2.3. The Ottoman Siege – A Hard Fight for Klis

One of the most dramatic phases in Klis's history was the Ottoman invasion. The Turks besieged the fortress for years until they finally captured it in 1537. Klis remained under Ottoman rule for over 100 years until the Venetians recaptured it in the 17th century.

2.4. Venetians, Habsburgs, and the Road to Modernity

After the Ottomans, the Venetians and later the Habsburgs took over the fortress. It was used for military purposes until the 19th century, before losing its strategic importance. Today, it is an important historical monument and a popular tourist attraction.

After the Ottomans, the Venetians and later the Habsburgs took over the fortress. It was used for military purposes until the 19th century, before losing its strategic importance. Today, it is an important historical monument and a popular tourist attraction.

3. The Architecture of Klis Fortress

3.1. The Impressive Structure

The fortress stretches over a length of 300 meters and consists of several defensive walls, towers, and casemates. Its location on a narrow rocky ridge, which allowed attackers to attack from only a few sides, is particularly impressive.

3.2. Key Areas of the Fortress

- Main Gate: The only access to the fortress, secured by several gates.

• Citadel: The highest point with the best view of the surrounding area.

• Chapel of St. Vitus: A small but important church within the fortress.

• Gun Platforms: Former artillery emplacements overlooking Split.

4. Klis Fortress Today – A Highlight for Visitors

4.1. Klis as a Film Set – Game of Thrones

In recent years, Klis Fortress has become world-famous as a filming location for the TV series Game of Thrones. It served as the backdrop for the city of Meereen, attracting many fans of the series.

In recent years, Klis Fortress has become world-famous as a filming location for the TV series Game of Thrones. It served as the backdrop for the city of Meereen, attracting many fans of the series.

4.2. Events and Festivals

Historical reenactments, medieval festivals, and cultural events take place in the fortress every year. The Knights' Festival in summer is a particular highlight.

4.3. The Fortress Museum

A small museum displays weapons, armor, and historical documents relating to the fortress's history. It's worth spending some time here.

5. Tips for your visit to Klis Fortress

5.1. Getting to the fortress

- By car: Klis is about 15 km from Split, with parking nearby.

• By public transport: Buses run regularly from Split to Klis.

• On foot: Sporty visitors can take the ancient pilgrimage route from Split to Klis.

5.2. Entrance fees and opening hours

5.2. Entrance fees and opening hours

- Entrance fee: Approx. €10 per person

• Opening hours: Open daily, until the evening in summer.

5.3. The best time to visit

- Spring & autumn: Perfect temperatures for exploring.

• Summer: Very hot, but long opening hours.

• Winter: Fewer tourists, but shorter days.

6. Conclusion: An unforgettable experience in Croatia

Klis Fortress is one of Croatia's most impressive castles and a must-see for anyone interested in history, architecture, or simply spectacular views.

✔ Unique history – From the Romans to the Ottomans.

✔ Incredible panoramic views – Perfect for photographers.

✔ Game of Thrones filming location – A highlight for fans of the series.

✔ Easily accessible from Split – Ideal for a half-day trip.

Whether you stroll through the ancient walls, enjoy the view, or simply soak up the special atmosphere, a visit to Klis is guaranteed to be an unforgettable experience!

7. FAQs about Klis Fortress

1. How long does it take to visit Klis Fortress?

1. How long does it take to visit Klis Fortress?

Plan on spending about 1.5 to 2 hours exploring at your leisure.

2. Are there restaurants nearby?

Yes, there are several restaurants serving local cuisine in Klis – be sure to try the traditional lamb dish "Janjetina."

3. Is Klis Fortress wheelchair accessible?

No, there are many stairs and uneven paths, making it difficult for people with limited mobility.

4. Is the visit also worthwhile for families with children?

Yes, but small children should be closely supervised in some areas, as there are steep drops.

5. Are there guided tours?

Yes, guided tours are available – the tours with historical narration are particularly exciting.

Immerse yourself in the past and discover one of Croatia's most spectacular fortresses!

Please read as well:

Fendt Caravan - First contact at Caravan Salon Düsseldorf

Porta Caesarea - a city gate of Salona

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

-

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

Klis Fortress - bulwark to Split

https://www.alaturka.info/en/croatia/split/6299-the-klis-fortress-bulwark-to-the-split-peninsula#sigProId47f96e8910