The Athos Monasteries Chalkidiki and the Hesychasm Dispute

- Written by Portal Editor

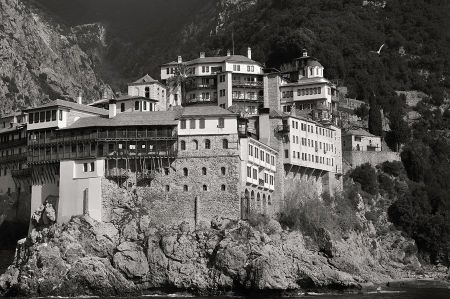

Of course, during our visits to Thessaloniki and Halkidiki we also discussed the monasteries of Athos, the way of life of the monks and a possible visit to the monastery complex several times. Ultimately, this is still pending, but has already been applied for.

Yes, that's right, a special visit permit with presentation of your passport is required for this part of Greece.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire and the division of the empire into Western and Eastern Rome, the Chalkidiki peninsula fell to Eastern Rome, from which the Byzantine Empire would later emerge. Although some researchers occasionally want to trace the beginning of the history of the monasteries and monastic republics on Athos back to the early Christian period, the first reliable evidence of monastic life on Athos that has been found so far can only be found at the beginning of the 9th century, i.e. during the Byzantine era.

The history of the Athos monasteries in the following centuries is closely linked to the dispute over the law-making, monastic life, which flared up violently again and again in Orthodoxy - and also on Athos: the so-called hesychasm dispute between the hesychasts and Byzantine humanists. Hesychasm is a form of spirituality that was developed by orthodox Byzantine monks in the Middle Ages. The term itself is derived from the Greek word hesychia, which means “rest” or “stillness”. Hesychia is associated with the ideas of serenity and inner peace.

Biographies of the early ascetics describe the corresponding practice

A prayer practice that corresponds to the hesychastic one in essential aspects can already be traced back to early church monasticism. The apothegms (sayings) of the “Desert Father” Antonio († 356), a hermit living in the Egyptian desert, and other early monks contain rules of conduct such as “keeping your tongue” to maintain vigilance and calm (hesychia). Biographies of the early ascetics describe the corresponding practice. These writings, which were influential in late antiquity and the Middle Ages, paint a picture of ideal monasticism. Above all, Antonio's authority had a strong impact; He was nicknamed “the Great” and was revered as an important saint and the forefather of monasticism. Closely linked to hesychia was nepsis, the monitoring of one's own thoughts and the rigorous rejection of all ideas and impulses that could be detrimental to inner peace.

A prayer practice that corresponds to the hesychastic one in essential aspects can already be traced back to early church monasticism. The apothegms (sayings) of the “Desert Father” Antonio († 356), a hermit living in the Egyptian desert, and other early monks contain rules of conduct such as “keeping your tongue” to maintain vigilance and calm (hesychia). Biographies of the early ascetics describe the corresponding practice. These writings, which were influential in late antiquity and the Middle Ages, paint a picture of ideal monasticism. Above all, Antonio's authority had a strong impact; He was nicknamed “the Great” and was revered as an important saint and the forefather of monasticism. Closely linked to hesychia was nepsis, the monitoring of one's own thoughts and the rigorous rejection of all ideas and impulses that could be detrimental to inner peace.

The realization of hesychia is achieved through persistent practice within the framework of a special prayer practice. The praying hesychasts repeat the invocation of the Jesus prayer over long periods of time. They use a special breathing technique to help promote concentration. The aim is to achieve a state of complete peace of mind, which is considered a prerequisite for experiencing a special divine grace: According to the Hesychasts, those who pray can perceive the uncreated Tabor light in a vision. The Tabor light refers to the light that Peter, James and John saw on a mountain at the transfiguration of Christ, according to the account of the three synoptic gospels. According to extra-biblical tradition, the mountain is Mount Tabor, which is why the light is called the Tabor light. The doctrine that God himself is present and visible in the uncreated light has been part of the core of hesychastic beliefs since the late Middle Ages.

To see the light of Jesus' transfiguration, the so-called "Tabor light".

The spokesman for the hesychastic side was the Athos monk Gregorios Palamas (1296/1297–1359), who saw complete inner peace in hermit-like solitude through constant prayer of the Jesus prayer as a prerequisite for the light of Jesus' transfiguration, the so-called "Tabor light" to see. His theology provided hesychastic practice with its theoretical foundation and justification. Palamas defended hesychasm against the criticism of Barlaam of Calabria, who criticized mystical practice and its justification through the writings of Gregorios Palamas in the spirit of a nominalist humanism. At several councils in Constantinople between 1341 and 1351, the Byzantine Church decided to first condemn the opponents of hesychasm and then to elevate the theoretical justification of hesychasm by Gregorios Palamas (“Palamism”) to binding church doctrine.

The spokesman for the hesychastic side was the Athos monk Gregorios Palamas (1296/1297–1359), who saw complete inner peace in hermit-like solitude through constant prayer of the Jesus prayer as a prerequisite for the light of Jesus' transfiguration, the so-called "Tabor light" to see. His theology provided hesychastic practice with its theoretical foundation and justification. Palamas defended hesychasm against the criticism of Barlaam of Calabria, who criticized mystical practice and its justification through the writings of Gregorios Palamas in the spirit of a nominalist humanism. At several councils in Constantinople between 1341 and 1351, the Byzantine Church decided to first condemn the opponents of hesychasm and then to elevate the theoretical justification of hesychasm by Gregorios Palamas (“Palamism”) to binding church doctrine.

Hesyachism has been able to establish itself permanently in the Orthodox churches, but outside of Orthodoxy it has largely met with rejection or reluctance. Critics have always been offended by the claim that something uncreated and therefore divine can be perceived. The objection is that this is impossible because of God's absolute transcendence. Controversial debates continue to the present day. Hesychasm, with its promise of direct personal access to the deity, is often viewed as a counterpoint and alternative to a discursive search for truth fraught with uncertainty. Hesychasts reject the use of a philosophical method in theology. The influence of hesychasm and palamism has permanently discredited the striving for a synthesis of philosophy and theology in the sense of the Western scholastic approach in the Orthodox world.

Hesyachism has been able to establish itself permanently in the Orthodox churches, but outside of Orthodoxy it has largely met with rejection or reluctance. Critics have always been offended by the claim that something uncreated and therefore divine can be perceived. The objection is that this is impossible because of God's absolute transcendence. Controversial debates continue to the present day. Hesychasm, with its promise of direct personal access to the deity, is often viewed as a counterpoint and alternative to a discursive search for truth fraught with uncertainty. Hesychasts reject the use of a philosophical method in theology. The influence of hesychasm and palamism has permanently discredited the striving for a synthesis of philosophy and theology in the sense of the Western scholastic approach in the Orthodox world.

The medieval hesychastic movement had its centre in the monasteries and skites on Mount Athos. During its heyday in the late Middle Ages, it also spread to the northern Balkans and Russia. After the destruction of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans in the 15th century, hesychastic practice faded into the background in the former Byzantine areas. However, the tradition did not break off and was continued in Russian monasticism in the early modern period. From the 18th century onwards there was a “neo-hesychastic” upswing, the consequences of which continue to be felt in Orthodoxy. In the early 20th century, the Imjaslavie movement continued the hesychastic tradition.

The medieval hesychastic movement had its centre in the monasteries and skites on Mount Athos. During its heyday in the late Middle Ages, it also spread to the northern Balkans and Russia. After the destruction of the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans in the 15th century, hesychastic practice faded into the background in the former Byzantine areas. However, the tradition did not break off and was continued in Russian monasticism in the early modern period. From the 18th century onwards there was a “neo-hesychastic” upswing, the consequences of which continue to be felt in Orthodoxy. In the early 20th century, the Imjaslavie movement continued the hesychastic tradition.

Remarkably, 550 years later, at the turn of the 20th century, this theological dispute between realists and nominalists, between rationalist theorists and theologians oriented towards mystical practice, was repeated on Mount Athos and emerged as a dispute over the Imjaslavie movement, the veneration of the name of God, into the history of Athos and Orthodoxy.

Pictured: St. Gregorios Palamas Church in Thessaloniki, where the relics were found!

Please also read:

Olympus - Exploration via the eastern entrance from Litochoro