Coinage - History of the Means of Payment "Coin"

- Written by Portal Editor

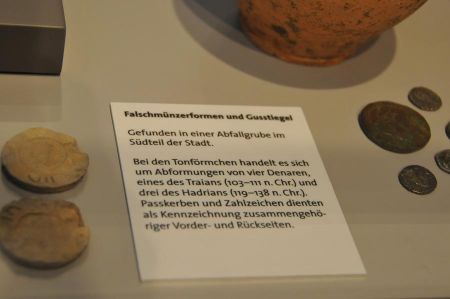

Coinage - During our travels through the ancient cities and the associated visits to museums in the various regions of Asia Minor, we often encountered coin collections in the exhibitions that were already used as a means of payment in antiquity.

Sometimes barely recognizable as having been minted by humans, these finds nevertheless help in the historical context of the development of human settlement. Trade existed even in antiquity, but payment was almost always made through barter. Quite often, due to inaccuracies in bartering, one of the trading partners felt cheated, and not infrequently, bartering opened the door to fraud.

Despite the diverse finds in Asia Minor and Greece, a concrete transition from bartering to payment with coins (coinage) can only be understood as a gradual process. The oldest finds to date point to around 2000 BC, as the bronze pieces found exhibit certain characteristics of their use as means of payment, distinguishing them from jewelry. The depiction of domestic animals imprinted on the metal suggests its use as a means of payment. The significant advantage of coins in commerce was so pronounced that they spread rapidly over large areas: coins were uniform in size, weight, and appearance, could be counted instead of weighed, and, most importantly, possessed the intrinsic value of their intrinsic material—gold, silver, or bronze—which should not be underestimated, especially from today's perspective. This intrinsic value served as a measure of preservation.

Despite the diverse finds in Asia Minor and Greece, a concrete transition from bartering to payment with coins (coinage) can only be understood as a gradual process. The oldest finds to date point to around 2000 BC, as the bronze pieces found exhibit certain characteristics of their use as means of payment, distinguishing them from jewelry. The depiction of domestic animals imprinted on the metal suggests its use as a means of payment. The significant advantage of coins in commerce was so pronounced that they spread rapidly over large areas: coins were uniform in size, weight, and appearance, could be counted instead of weighed, and, most importantly, possessed the intrinsic value of their intrinsic material—gold, silver, or bronze—which should not be underestimated, especially from today's perspective. This intrinsic value served as a measure of preservation.

Under the Lydian king Alyattes II, the use of coins as a means of payment progressed further. King Alyattes II is credited with the use of naturally occurring, lumpy electrum nuggets, which he had minted and sealed with his royal seal between 650 and 620 BC and used as coinage currency. These nuggets were frequently found in riverbeds as irregularly shaped, natural lumps of a gold-silver alloy, which, after rough processing, were used as money.

Even today, stories and proverbs about the inexhaustible wealth of the Lydian king Croesus, who reigned as the last king of the Lydian kingdom between 555 and 541 BC, sometimes concurrently with Alyattes II, are among the most frequently cited ancient rulers known for their prosperity and extravagance. "You live like Croesus" is, in common parlance, synonymous with "very lavish and generous." Croesus amassed his wealth from mining between Atarneus and Pergamon and along the Pactolus River in search of gold, and above all from the tribute payments of the cities he conquered, as well as taxes from trade and commerce. It is no wonder, then, that the gold, which was quickly melted, was also used in the production of coins.

Even today, stories and proverbs about the inexhaustible wealth of the Lydian king Croesus, who reigned as the last king of the Lydian kingdom between 555 and 541 BC, sometimes concurrently with Alyattes II, are among the most frequently cited ancient rulers known for their prosperity and extravagance. "You live like Croesus" is, in common parlance, synonymous with "very lavish and generous." Croesus amassed his wealth from mining between Atarneus and Pergamon and along the Pactolus River in search of gold, and above all from the tribute payments of the cities he conquered, as well as taxes from trade and commerce. It is no wonder, then, that the gold, which was quickly melted, was also used in the production of coins.

The phrase "You live like Croesus" is, in essence, synonymous with "very lavish and generous." Croesus acquired his wealth from mining between Atarneus and Pergamon and in the Pactolus River in his search for gold, and above all from the tribute payments of the cities he conquered, as well as taxes from trade and commerce. It is no wonder, then, that the gold, which was molten very quickly, was also used in the minting for coinage.

Compared to other rulers of the time, especially the Persian kings, Croesus's wealth wasn't actually that immense. However, this impression spread rapidly throughout the world because the Lydian coins, made of pure gold and bearing the seal and the animal symbol of a lion or bull, conveyed an image of great wealth and were widely used as currency. The coin's name itself speaks volumes: the "Croiseus." The remains of his palace buildings in the city of Sardis, near Izmir, also suggest considerable prosperity.

Compared to other rulers of the time, especially the Persian kings, Croesus's wealth wasn't actually that immense. However, this impression spread rapidly throughout the world because the Lydian coins, made of pure gold and bearing the seal and the animal symbol of a lion or bull, conveyed an image of great wealth and were widely used as currency. The coin's name itself speaks volumes: the "Croiseus." The remains of his palace buildings in the city of Sardis, near Izmir, also suggest considerable prosperity.

Around the same time, the first silver coins were minted on the Greek island of Aegina, which also quickly became widespread as currency. By about 400 BC, the use of coins in trade was fully established in Asia Minor and Greece, and goods were now being paid for. The coins from the Aegina region were called tortoises because their animal symbol depicted a tortoise. Similarly, the coins from Corinth showed the animal symbol of a foal, and the coins from Athens the symbol of an owl. The phrase "carrying coals to Newcastle" is currently very topical again.

However, since there was no unified monetary system, the now familiar problem of exchange rates soon arose, as each region minted its own coins. Gradually, a standardized 17-gram coin, the Attic tetradrachm, was introduced. However, its parallel introduction as a subsidiary coin (the metal value of the coin does not correspond to the face value printed on it) laid the foundation for today's global currency transactions.

However, since there was no unified monetary system, the now familiar problem of exchange rates soon arose, as each region minted its own coins. Gradually, a standardized 17-gram coin, the Attic tetradrachm, was introduced. However, its parallel introduction as a subsidiary coin (the metal value of the coin does not correspond to the face value printed on it) laid the foundation for today's global currency transactions.

Refining working methods allowed for new motifs to be minted on the coins. In addition to the animal portraits produced previously, it was primarily the various figures of gods that were depicted on the coins. Since minting was still done with a hammer and anvil, many coins were incompletely formed, especially at the edges, and showed cracks. After the reign of Alexander the Great, secular rulers were increasingly depicted on the coins, although silver remained a component of the coinage, a practice that continued into modern times until just a few years ago.

Location in Zurich:

MoneyMuseum

Hadlaubstrasse 106

CH-8006 Zurich

Opening hours: Tue and Fri 1:00–5:30 pm

Please also read:

Cyprus - Wintering on the (still) divided island

Karmi (Karaman) - idyllic mountain village near Girne